Video

Video Interview: Jeremy Oates

Date

February 3, 2007

Duration

82:23

Archive ID#

Description

The Roaring Fork Veterans History Project

In Association with Aspen Historical Society and the

Library of Congress Presents: Jeremie Oates

U.S. Army

Bosnia: 1998-1999

Global War on Terror: 2006-2012

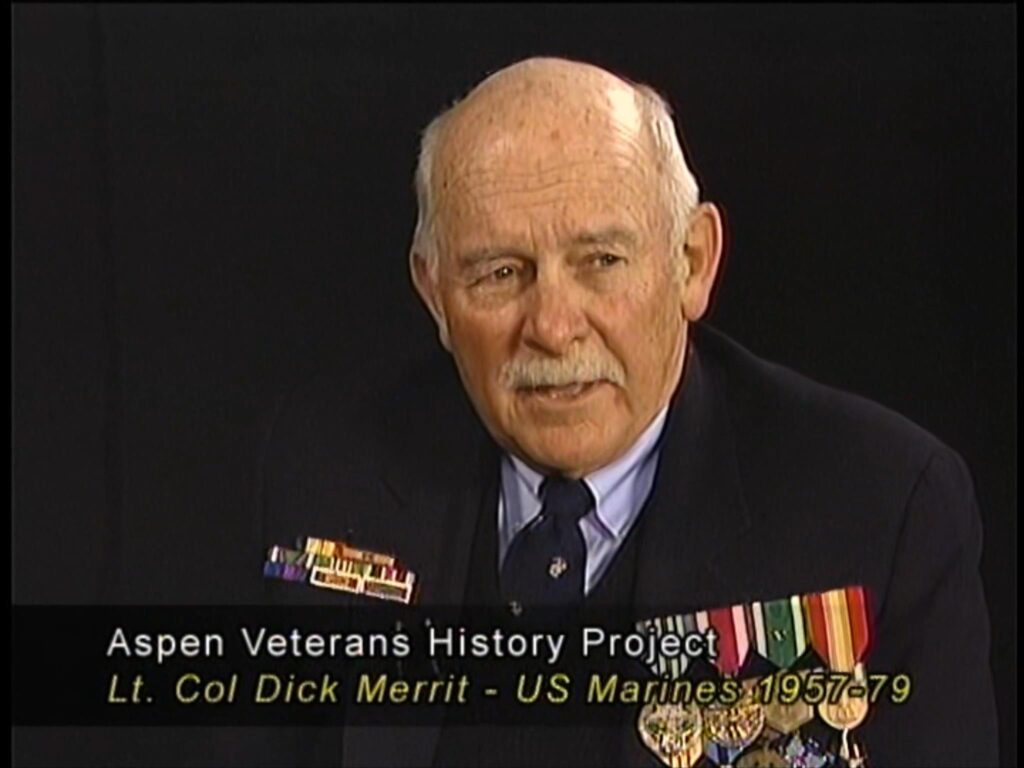

Interview conducted by: Lieutenant Colonel Dick Merritt

Transcribed by: Agren Blando Court Reporting & Video, Inc.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Today is 20 November 2012. We are at Aspen Community GrassRoots Television, Aspen, Colorado. Today we’re interviewing Jeremie Oates. Jeremie was born April 3, 1970 in Aspen, Colorado. He’s a native of our city. Our camera operators are Patrice Kahn and Richard Lampine (ph) and coordinated by Rye Zypanus (ph).

The organization that we’re working for today is the Roaring Fork Veterans History Project.

I’m Lieutenant Colonel Dick Merritt, United States Marine Corps, retired.

Welcome, Jeremie. Good to have you here.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, thanks for having me, Dick. I appreciate it.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, I’ve known you since you’ve been nine years old. And your brother and my son grew up together in hockey and all that, and so you’re very much a part of that. And I followed you through your high school career and through college. And I was very honored to commission you in the Army 20 years. So where did the last 20 years go? Here we are today sitting in this studio in Aspen. So it’s good to be with you.

Jeremie, can you tell us about your branch of service and when you retired from the Army?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, I actually joined the Army in 1990 — early 1990 and went into the Army Reserves initially, and I was an enlisted soldier there for about two years. And then through the University of Colorado Boulder ROTC program, I was commissioned, as you mentioned, as an infantry officer on active duty in 1992.

And from there, I served, you know, pretty much all over the world for 20 years as an officer. And then I just recently retired as a Lieutenant Colonel on the 1st of October.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Where did you serve, Jeremie?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, in the — you know, in the United States in CONAS, as it’s called, you know, multiple locations. I served in Fort Campbell, Kentucky; Fort Benning, Georgia; Fort Carson, Colorado; MacDill Air Force Base down in Tampa, Florida. So that was the bulk of my service in — and Fort Bragg, North Carolina for the last six years.

And then outside of the United States, I served in Alaska, in Fort Richardson, served at multiple locations in Germany with my family. And then as far as deployments, I deployed all over Eastern Europe. Deployed to Bosnia, Herzegovina. And I deployed to Afghanistan and Pakistan on five different tours from 2006.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, I had served 20 years in the Marine Corps and I served six years in Asia, and I thought that was a lot of time overseas. But how many years did you serve overseas?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, all told, to include the tours in Europe, probably about eight years.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: About eight years —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Eight or nine years.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — out of twenty.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: That’s a long deployment.

Can you tell me a little bit about your training in ROTC when you were at Colorado — University of Colorado?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah. Well, I — you know, as I said, I kind of — my military experience started with the Army National — or the Army Reserves here in Colorado. And that was sort of a mixed experience. You know, not — I wouldn’t say necessarily, you know, found a lot of mentors there, although I — you know, I did have some good friends and some good kinship. I actually enlisted with Bobby Williams, who was another, you know, long-time local kid in Aspen, an Aspen High School graduate.

And so we enlisted together and, you know, didn’t really find any mentors or any real sort of examples in leadership, I don’t think, that I would aspire to. But once we went into ROTC, I mean, definitely some great mentors, officers, and NCO’s. And it was a great four years there. You know, I learned a lot, I think about leadership and sort of enduring lessons about, you know, how to treat people in my experience there. So it was a great program and kind of unique too to be in — you know, in this ROTC program at the University of Colorado, which is, you know, Boulder and pretty liberal experience overall. So it was unique in a number of ways.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: At that time around when you were commissioned, Bobby Williams who — Andy Williams’ son, Aspen, he went into the Army, didn’t he —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: He did actually. He — you know, again, great guy, you know, my best friend growing up. He kind of went a different way and he ended up going into the — he actually went into the Special Forces in the National Guard, the 19th Special Forces Group, went through the qualification course, so he was a full-fledged Special Forces soldier. And he ended up deploying in the mid ‘90s to multiple locations to include a six-month tour to Haiti in support of the UN peacekeeping efforts there. So he definitely did his service, albeit in kind of a different way.

And then more recently, he actually had left the service, but continued to do great service through his documentary filmmaking endeavors to support Special Operations troops and kind of tell the story about what we do and why it’s so important to recruit, you know, the best and the brightest from the rest of the Army, or the military for the other Special Operations Forces in the other services.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, I’d like to get Bobby up here and interview him for the Roaring Fork Veterans History Project, like you’re doing today, because he has a story.

I’ve — you know, a good friend of mine is your father, Lenny, and Lenny was in the Marine Corps at 29 Palms. Did he impart any words of wisdom to you before you went into the Army as a career? You’re a career man.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. Well, he — you know, he’s definitely, you know, proud of his country and I think proud of his service. And he was — you know, it was a different time in Aspen in the ‘70s and ‘80s, you know, when I was a kid. I mean, there was a definite sort of — I would say kind of anti-military or anti-patriotic feeling in the town. And it was a product largely of, as you know, of Vietnam and sort of the hangover of that experience, and, you know, just sort of the mountain town sort of left leaning sort of types, which was fine. I mean, it was a diverse environment and everybody’s entitled to their opinion. But my father was sort of to the right of that by quite a ways, as you know. And so he — you know, he and my mother, I mean, they imparted a lot of patriotism and, you know, volunteerism and, you know, you should be proud of your country and if you can do something for it, you should make that effort. And so that — you know, it sort of pushed, you know, each of us — you know, myself, my brother and my sister into sort of different directions.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Service.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: But, you know, service was an important thing, as it should be. And, you know, love your country is an important thing, as it should be. You know, I think — I think we’ve gotten better about that and I certainly see the outreach to Veterans of my generation being a lot more supportive than it certainly was for you guys, and that’s a good thing.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: As a Vietnam Veteran, I lived in Aspen ten years before I really came out. That was when the Vietnam Memorial was dedicated, and that was 25 years ago. And then finally, I started marching in the Fourth of July parade, which I hope you’ll march with us this summer because it’s a standing ovation and it’s kind of a welcome that we never got from Vietnam, and so things have changed a whole lot.

And then we do have the Veterans Memorial, I mentioned. We — you were there with us on — last week on Veterans Day in the cold and we always honor our Veterans on Veterans Day and Memorial Day, so we hope that you will continue to join us.

And then, you know, in the military, there are a lot of things, places that you’ve been that you mentioned all over the world that are really quite exciting. And I’ve read about some of your travels. Even though you’re in active duty in the Army, my good friend, Charlie Hopton served in Korea. And I read in the paper and Charlie told me about your trip up Mount Lenin. Can you — can you tell us about that, where it was and —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah. Yeah, that was a

— it’s kind of an interesting story. I mean, one of the other things that was really important, you know, growing up here as a kid in Aspen was, you know, a lot of the outdoors and we had, you know, the outdoor education program and experienced educational program in the public school, so, you know, kids were exposed to the mountains and the out of doors and I kind of carried that into my adult life with climbing mountains. I got to go — you know, I had the opportunity to go all over the world, actually, in my adulthood to climb some pretty significant peaks.

But Peak Lenin was interesting in that this was, you know, before 911. It was in the late ‘90s. And we went on the trip. It was myself and Mike and Steve Marole (ph), Jim Gall (ph), some other, you know, Aspen local kids that had grown up here.

And so we were really, you know, in the environment, so to speak, in terms of that, you know, central Asia and the rise of that Islamic militancy, some of the turbulence from the breakup of the former, you know — the former Soviet Union and those republics in Central Asia. So it was kind of a walk back in time. I mean, we were, you know, transcending through these bases that were abandoned or half abandoned. I mean, there would be a small civilian airport or a bus station, and then the other half of it was full of abandoned Soviet vehicles and all that sort of refuse of war after they had pulled out of Afghanistan in 1989 and then the Soviet Union had collapsed shortly after that.

So it was interesting and there was a lot of sort of nefarious characters running around. I mean, it was a rise of sort of some Islamic fundamentalist movements in Kurdistan and Tajikistan, and to a large extent, Kazakhstan. And who would have thought, you know, we went on this trip and we were kind of out there, I wouldn’t say in a super dangerous area, but it was certainly on the periphery of a dangerous area. Tajikistan had just gotten done with a pretty nasty civil war when we were there that there were, you know, tens of thousands of people killed in.

And so we went to the mountain and we — we didn’t end up summiting, but, you know, we ended up getting up pretty high in the mountain. But the — you know, the experience, it turned out later, was just being in that environment, getting to know some of the people there. And then, you know, who would have thought, you know, three years later that I would be back in the same place in Manas Transit Center, it’s called, which was this airport in Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan that, you know, now there’s a big American base there after 911 and to this day, I mean, before that there was nothing there, you know. And we were just sort of — we were just sort of tourists to the whole thing. And then to be back there in uniform was kind of a unique experience.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Really amazing because who would have thought, you know, 57 years ago, my time in the Marine Corps when I started, it would never have been — dreamed of any officer going to the Soviet Union. I was in Germany in August of 1961 when the Berlin Wall went up, and I was away from the Marine Corps and I thought, ah-oh, this is the start of World War III and here I am, there’s no Marines, I’ve got to get back to the States, and it was a scary time.

So how did the Army allow you to take time to go to Mount Lenin?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: I mean, you must have had some type of special dispensation to do that.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. Well, this was — you know, keep in mind — I mean, this was a few years after the breakup of the Soviet Union. And really, I mean, particularly in the Special Operations community, I mean, there was a significant effort before 911 to go out and court these former Soviet Republics, I mean, really to try to bring them into our sphere of influence. You know, not necessarily as a way to subvert any control of the Soviet Union, but to sort of continue to play the great game in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

So that was an effort. I mean, we weren’t at war — you know, a shooting war, but we were clearly trying to bring into our sphere these countries. And you can see that it was largely effective because you’ve got a lot of the former Soviet Republics and those former Warsaw Pact Nations which are now in NATO and providing troops to support —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: To support, yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — to support the war in Afghanistan and formerly the war in Iraq, and we’re using a lot of the bases — former Soviet bases in those Central Asian Republics to support the war in Afghanistan, in terms of, you know, transit centers, and basing for aircraft, and, you know, ability to move troops and equipment over vast distances because, you know, Afghanistan is arguably the hardest theater of war that we’ve ever had to conduct logistics in just because it’s so isolated.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, another expedition, if my memory serves me right, we were on efforts with the Maroques?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, I did. That was another trip a couple years later. I did have the opportunity to do that. Again, sort of a unique case. And one thing about, you know, the Army Special Forces and I can thank a lot of my — you know, the great leaders I had is that our environment to operate in is human terrain. I mean, it’s not the sort of three — you know, it’s not the terrain or in a battlefield. I mean, it’s personal relationships. It’s understanding cultures. It’s understanding, you know, why people do what they do and being able to kind of blend in, to a certain extent, or at least identify some common ground so that we can, you know, take what shared objectives we have and morph those into kind of a campaign plan or a way forward.

And so it was a great opportunity to be able to do

— you know, the Army looked at it, I think for me as a great opportunity to go out and kind of refine those skills. And, you know, maybe we’re not going to go back to those places ever to engage in any sort of a, you know, a campaign plan or an unconventional warfare campaign, but, you know, the more you’re able to identify with different cultures and you’re able to build those sort of skills and those tools for rapport building, the better it serves you. And really, I mean, that’s — you know, when you go into an unknown environment dealing with very different cultures, whether it’s, you know, in Asia or wherever, the more kind of comfortable you are and the more skills you have to sort of, you know, build that rapport and build those relationships, it’s critical to achieving anything.

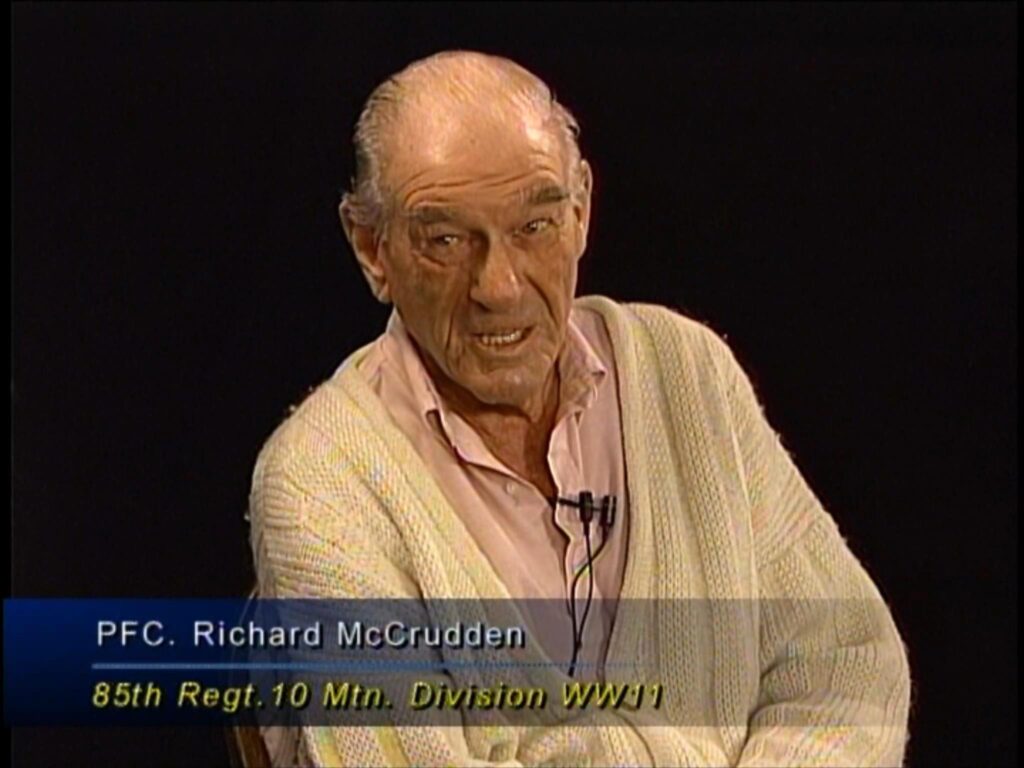

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Speaking of skills, Jeremie, if we were in the World War II era, you would be a prime candidate for the 10th Mountain Division, because the 10th Mountain Division fought through Italy. And in order to form that up, they recruited skiers and mountain climbers and even Europeans with that background —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — and fought that war. And so people with special skills, as you mentioned, we’re looking for in the Marine Corps. We have a command called the Mountain Warfare Training Command today where we will send infantry battalions there for three weeks training in the high Sierras where we’re 10, 11, 12,000 feet to go to Afghanistan. So that skilled training is still going on because I would guess at those higher altitudes, it’s just as cold there as it is here.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, on the note of the 10th Mountain Division, obviously that kind of figured in my formative years a lot as well. I mean, growing up in Aspen everybody knows — has heard about the 10th Mountain Division, knows a little bit about its storied history. And, you know, my childhood — I mean, a lot of the sort of town fathers whether it was Freidl Pfeifer or, you know, some of these other —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Fritz Benedict.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — Fritz — yeah, Fritz Benedict.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Steve Knowlton.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: The list goes on and on and on.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, the list goes on and on. Or Bill Dunaway.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Bill Dunaway, yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: You know, that was an important sort of a thing. And interestingly enough, my great uncle George Czakowsic (ph), who was an Aspen native, my grandmother’s brother was actually one of the plank holders — one of the founding members of the 87th Infantry Regiment. So he was a member of the 10th Mountain Division before the Division even existed. It was a just a regiment up at Paradise Lodge up in —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Right. And that’s —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — up in Washington, right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — that’s where I’m from, that area, and all the well-known mountain climbers joined the 10th Mountain Division. The skiers then — and one of them, his name is Jim Whitaker, and he was in the Cold Weather Command over at Camp Hale, and he was the first American up Mount Everest. And he took me up Mount Rainier — guided me up there in 1954. So there’s this connection of people like — well, like us — skiers and mountain

climbers —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — that tend up to wind up in the military in some way, shape or form.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Absolutely.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Yeah. Well, Jeremie, we’ve talked a little bit about your commissioning and Bobby Williams. Let’s go to some images and run through them and if you would explain to us what we’re about to see here on the screen.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, actually, this is one of my favorite pictures. This is actually myself on the right there and then Bobby Williams, who we talked about, on the left. This was the day we graduated from basic training as Privates in Fort Benning, Georgia, so that would have been in August of 1990.

Interesting times. I mean, the — you know, the wall was coming down and, you know, there was a lot of questions about what the future of the military was even going to be and, you know, I think — or, the — you know, the future of the Army. You know, it was already a peace (indiscernible) from the Cold War. And then about halfway through that training was when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in the first Gulf War, so we were sort of nervous about what was going to happen. And we ended up — I ended up not deploying, but Bobby ended up deploying for about six months over to Germany to support some of the activity over there that was supporting the war in the Gulf there. So that was an interesting time.

And for that graduation, it was great because Claudine Longet, Bobby’s mom, actually ended up coming — or Claudine Austin ended up coming down to support our graduation, so that was pretty cool. And we thought we were a big deal because we were, you know, Privates in the Infantry in the Army. So it was a good time. Little did we know, you know, we were both, you know, kind of go on in different ways to have, you know, a lot of unique experiences through the Army and through the military.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Okay. Then the next one there, Jeremie.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, this is — you know, fast forward about 15 years. And this is a picture of me with, you know, body armor and all that on in Kabul, Afghanistan. This was a few years after the fall of the Taliban. And, you know, you can see that’s kind of a typical Kabul landscape. You know, it’s a city of 2 million people, very poor, you know, a lot of different ethnic groups kind of thrown together there. It’s at a pretty high altitude, so you can see, you know, there’s not a lot of vegetation there. And in the winter, it’s pretty — it’s a pretty rough place to be. And actually, that was a clear day. Most of the time, it’s all socked in because people are burning wood, you know, and animal dung and coal and things like that for all their heating and cooking. So that was a unique day there.

And also interesting about that is that was kind of a turning point at that time in Afghanistan. I mean, if you recall, I mean, after the fall of the Taliban, it was pretty quiet for about three or four years. I mean, we had focused our efforts in Iraq. The Taliban had been pretty much dispersed and had, you know, a significant number of them had been killed. In 2001, you know, when we initially invaded or initially, you know, came to the aid of the Northern Alliance, but kind of by 2005, 2006, they had reconstituted. So this was really the turning point at that winter of 2005, 2006 when it kind of went from that latent insipient phase of irregular warfare to really full-on guerilla warfare.

And so by the time I returned the next summer, in the summer of 2006, end of 2007, that’s when you really saw the war sort of, you know, flare up again. And we’ve — you know, we’ve seen it kind of maintain that pitch ever since. So it definitely speaks to the resiliency of the — of those malign actors in Afghanistan, whether it’s the Taliban or any of the other, you know, accounting network or any of these other acts that are kind of vying power.

And I think — my opinion is they’ll maintain that tempo, you know, through when we leave, and then it will be interesting to see what the government of Afghanistan does to sustain itself or to sort of sustain the country as a viable entity.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: All right. Then what do we have next then?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah. This is another one of my favorite pictures. This was the day that I got commissioned to Lieutenant Colonel, so that would have been in the kind of in the spring of 2009. And did that at Fort Bragg. There’s sort of a memorial walkway there that you can see part of and, you know, one of the statues there of the — to the Special Forces Regiment. So I was able to have my wife, Sally, and the kids there for that day and I got promoted by the commanding general. You know, it was pretty special. It’s always nice to be recognized, you know, and for all the great guys you work with to be recognized to a certain extent as well for — you know, for your being promoted all their support they provide to you, and to thank your family.

You know, that’s kind of the unsung story of the military is the families, as you know. I mean, I would tell you, Sally, my wife, who’s also a kid that grew up in Aspen. We’ve been married for about 18 years, you know, was really a single parent for years and years. And we talked about how long I was deployed for and those sort of back-to-back deployments where you’re gone for six months, come back for three weeks, and gone for another six months. And — I mean, she really was a stalwart and is kind of an example of a lot of the great wives that are out there.

For the kids, I mean, it was an interesting way to grow up, I know, but I think they were happy when it was over and we could come back here to Aspen and sort of, you know, live a little bit more settled and normal life.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, you’re doing exactly the same thing I did. My kids were two years old when I retired. I was a little bit older than you when I retired, but still the path is parallel. And your daughter and son — your son there about four years ago he was up on Buttermilk skiing with you and your mom, Sherrie, and I saw him take off down the mountain. And as fast as we could ski, we couldn’t catch that little guy, so he’s going to have a great growing up here in Aspen on the ski hill, along with your daughter.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: So we have another photo there that’s coming up.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, this is a picture from Pakistan. That is actually up in the Swat Valley. And this is interesting in that this was sort of my — one of my last tours in the Army — or in Special Forces, and it was my longest tour because I was basically gone from June of 2010 to December of 2011 in Pakistan, one of our allies in the way on terror, a difficult ally, and a challenging ally to work with, but an ally nonetheless. And so we did a lot of things over there to try to build that partnership and that relationship.

And this was one of those efforts. Actually, this was a humanitarian assistance mission from the flooding that occurred in 2010, which was kind of a double whammy for the Swat Valley there. As you recall, in 2009, the valley was overrun with fundamentalist militants who killed a lot of the local leadership that was loyal to the Islamabad government and killed a lot of Pakistani security forces before the Pakistani military could actually re-secure the valley.

And it took them about five divisions worth of troops to do that, along with, you know, Apache — or Cobra helicopters and F16’s and artillery, so that Swat had really suffered badly there, the population and the infrastructure. And so it was just sort of starting to get back on its feet and these floods happened in 2010, which really destroyed whatever was left from the battles that had occurred about nine months or a year earlier.

So we did a pretty extensive effort, in addition to our efforts had — you know, help build our sort of day job which was build capacity and capability in the Pakistani army to help them fight this Islamic militancy.

We transitioned to humanitarian assistance, and it was a combined effort or joint effort with the U.S. Army and the Marine Corps. We shipped a lot of assets from the Continental U.S. and from Afghanistan, and even a few from Iraq to support this calamity when it occurred. And really, the — you know, when I say it was a, you know, a flood, I mean, it really doesn’t do justice to what happens when that Indus River and the tributaries overflow its banks.

I mean, the river in some places during this flood was like 60 miles wide and everything in its wake was destroyed or damaged. A lot of human suffering, a lot of death, a lot of property loss. And up in Swat, we were — you know, a lot of those mountain communities, you know, kind of similar to Aspen here, similar elevations even were really isolated due to this flood. So we got some helicopters in there and we were able to help resupply those villages, bring people down to population centers where they could get medical treatment. So it was a great effort.

And, you know, up to that time, we’d done a lot of other things that was very beneficial to the Pakistani population. But unfortunately, the narrative sort of turned negative after that with WikiLeaks, with the constant sort of Pakistani Army, NATO, ISEF, you know, engagements on the border there between — on the Durand Line between Afghanistan and Pakistan and then, of course, the Osama bin Laden raid. So we sort of — you know, all the goodwill we’d built up to that point — or to those points was sort of evaporated fairly quickly and we were sort of at an impasse with Pakistan.

And I think the situation was still evolving at this point. I know we still had a heavy engagement with Pakistan, but our portion of it — the effort, which was to try to assist the Pakistani army to combat that militancy really is

— I could — I would call it failure at this point.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: That’s understandable. As military men, you know, the mission of the military success in combat and then I think a lot of people don’t realize the humanitarian things. The Marines came in from the aircraft carriers to the Indicen (ph), you guys did your thing. And so all these things are going along with that we are humans — humanitarian and not barbarians. We have our mission militarily, but we do a lot on the side.

Now, in that photo there, it shows a — what’s that on your face there, Jeremie?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, that was a — you know, that’s — everybody wants to talk about that and our commanding generals and Special Forces are always sort of gun shy about the topic of beards.

But in this case, I would tell you, I mean, there are a lot of places in Pakistan and some of the things we were doing up there in the Swat Valley where it is a dangerous place to be a Westerner. And so a beard from a forest protection standpoint makes a lot of sense.

In this case, I was wearing a Pakistani army uniform there. That’s another thing our generals find sort of a contentious thing with the laws of land warfare and all those kind of things, but, you know, that was something that the Pakistani army insisted on so that we weren’t identified for some of the things we did as foreigners because they’ve got as much of a domestic threat against their own government from these Islamic fundamentalist groups and the political parties that they’re allied with, as they do from anywhere. So there’s sort of a stigma about Americans being in certain places in Pakistan.

So we wear the beards, one, to not mark ourselves as Americans for our own safety; but two, to kind of safeguard that relationship with the Pakistani military.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Did you ever wear any native costumes?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: We did. Depending on where we were going, you know, in this case, I had a Pakistani uniform on so that you look like a, you know, from a distance anyway, a Pakistani because there are plenty of, you know, fair-skinned, you know, blue-eyed lighter haired Pakistanis, particularly out in the federally administered tribal areas and the Khyber-Paktunkhwa Province. But sometimes we would wear, you know, the shalwar kameez, which is their sort of ethnic dress, particularly out in those Pashtun areas just to kind of be a little less obtrusive and a little bit less obvious about what we were doing.

And when I say that, I mean, we weren’t doing anything to necessarily, you know, subvert the Pakistani government or anything like that, but, you know, in order to help them, we had to have access to places where, you know, to the general population and particularly to the Pashtuns out in those areas along the border. You know, the presence of Americans is something they see as a threat, and it’s something that the Pakistani government sees as a — you know, in their least in their public display as a sign of weakness. A lot of pride, a lot of sort of honor within the Pashtuns and the Panjabi Pakistanis, so they will take help, but they will take it, you know, sort of from a distance. So that was another reason for our mode of dress and our, you know, our grooming standards.

And it worked in the most part — for the most part. We had one incident where we did have three Americans killed in action and two wounded with a — due to a roadside bomb and they were trying to employ the forest protection measures that we had in place with the native dress and with the beards, but unfortunately, they were just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

But, that’s — you know, the reality is it’s the face of kind of modern warfare.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: It is, yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: I mean, you’re going to

— the sort of uniformed, you know, sort of, you know, United States military against the Soviet military or the sort of conventional battles are largely sort of a thing of the past, in my view. I don’t they’re done forever, but certainly in this era with asymmetric warfare, I mean, we need to look beyond just the traditional, you know, roles and morays of war.

And, you know, people will say and make the argument, hey, we — you know, if we’re not in uniform and we’re not recognized as combatants, we are — we’re, you know — we’re violating the Geneva and Hague Convention and the laws of land warfare, and therefore, we’re — you know, we don’t — we’re not accorded those rights. But in my view, I mean, how many POW’s have been, you know, released unharmed by the Taliban or by al-Qaeda. You know, it’s like, well, hey, you could be executed with this — without being in uniform as a spy. Well, I mean, look at the majority of our POW’s have been executed —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: They have been.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — publicly — you know, in a public way on the internet or whatever. And so to me, I mean, I think that we need to look beyond the traditional norms of warfare to be successful in the modern battlefield.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, last December we had a surprise party for you, Lieutenant Colonel Jeremie Oates, at the Elks Lodge. It was Christmas and I think Sherrie wanted to surprise you. You were home on leave, you were still in active duty. And I was waiting for some guests and I went down from the third floor to the Elks at the entrance way there, and there’s Georgia Hansen. And I said, say, “Hey, Georgia, you know, we’re having a surprise party for Jeremie Oates and we’re waiting for him to come in.” And I saw this guy standing back there with a beard. I thought he was a mountain man and then you smiled and said, “I’m Jeremie Oates.” And I didn’t recognize you at all. And you came to the party in your beard, you know.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right, right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: And so I knew why — I had an idea why —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — and that’s —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, that was kind of — you know, kind of fun. In most cases, you know, our general officers and our leadership is pretty insistent on people shaving their beards off when they come back. But I was — I came straight — pretty much straight back to Aspen, so it was — I was kind of in a safe zone.

The other thing with the beard is beyond, you know, the sort of things I’ve discussed is that, you know, with the Pashtuns or the patons, as the Pakistanis call them, you know, in that culture wearing a beard is a sign of maturity and is a sign of sort of authority.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Masculinity.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Masculinity. And so, you know, their measure of how — you know, how much legitimacy you bring to the table for discussion a lot of times is how big of a beard you have. So the sort of measure is, you know, a fisted beard. So if you can hold the beard and it’s flowing out of the bottom of your first, then, you know, you’re a man essentially.

And so, you know, from a rapport-building standpoint, I mean, that — a lot of times going into talk to tribal elders or going into to talk to local leadership, you know, it kind of is an icebreaker, you know, and particularly with the, you know, the sort of guys that have never heard of an American — or have never met an American before, but they — you know, they’ve heard of Americans and, you know, our reputation overseas is we have horns and a tail and we’re out to do harm or, you know, destroy Islam. You know, if you can kind of come at them on their terms, it’s a great way to build rapport and build relationships and find some common ground.

You know, unfortunately for the Army as a whole, you know, the way they — or the Marine Corps, for that matter, the way we’re sort of arrayed or were arrayed in Iraq and Afghanistan, you know, you’ve got forest protection measures. And forest protection isn’t, you know, dressing in civilian clothes in a civilian vehicle riding in a — you know, around with a beard, it’s being in an up-armored vehicle with 100 pounds of gear and body armor and a helmet and everything on.

And in my experience, you know, going to engage a village elder or going to do, you know, for your female engagement teams to engage, you know, sort of an under-represented portion of the population, the females, that is not a great way to do that. That’s not a great way to build rapport. I mean, you can imagine if a bunch of guys even showed up here in the Roaring Fork Valley from the National Guard or from wherever saying, hey, we’re to help you and they’ve got — they’re sort of postured for war or postured in a threatening way. So that’s another reason why, you know, some unconventional methods are desirable in kind of modern combat.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, in Vietnam, we had civil action groups that would go out with the villagers

— and these were actually active duty Marines. And in that, we didn’t really have approach toward the female population.

Now, I know in Iraq we had women Marines going out in — you know, in meeting the females and trying to win over the hearts and minds. What was your experience with Army females working with the local populace, specific to the women?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, I mean, it was very positive. I mean, that’s — you know, that’s another aspect as kind of the future of warfare. I mean, you have to touch, you know, from an informational standpoint and an information-gathering standpoint, all segments of the population. And in a place like Afghanistan or Pakistan, a very male dominated culture, you know, females are very much underrepresented in any kind of discussion or dialogue and that’s unfortunate, and that’s something that using, you know, female engagement team or females to kind of bridge that gap is very important.

So, you know, the role of women in combat or women in modern combat is going to be critical to sort of being able to engage with these populations, you know. And it’s sort of a cliché, you know, winning the hearts and minds, that’s something more from your era.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: That’s my era, yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: You know, but from a modern standpoint, you know, engagement and information operations targeted at these populations is critical. And, you know, the shooting war is sort of what gets all the coverage, but that grassroots level engagement and that, you know, development and governance at a local level, redevelopment if the community has been destroyed through war or through an environmental event. You know, religious reform, those are grassroots things and you have to start at that village level or that — you know, the clan level or the tribal level. And, you know, the female population is something you have to deal with.

As an example, I mean, you know, gathering the sort of data for, hey, what are the basic human needs that we need to help this population with in order to sway them or to, you know, have them not gravitate towards radical Islam. And, you know, some of the things you’re not going to know unless you engage that female population.

You know, infant mortality or midwifery are good examples. I mean, the male-dominated society is not going to talk about those things candidly the way that those women will. You know, and that’s important. I mean, knowing that

— you know, as an example, in some places in Pakistan, I mean, there’s a 150 cases of infant mortality per thousand, you know, births. I mean, that’s significant. You know, that is something that is really a driver of instability in that environment. I mean, our — you know, the State Department will tell you, you know, above 50 instances of infant mortality per thousand births is an indicator of instability. And we have places in Afghanistan and Pakistan, it’s 150, 200, and that’s just infant mortality. It doesn’t count, you know, the women dying in childbirth and all those kind of things.

So once we’ve identified that as a, you know, root cause potentially of instability, then we can put resources against it to help, you know, that population in a productive way to move away from radical Islam, move away from lawlessness. And, you know, it’s in a way that, you know, they don’t have to love the United States. I mean, they just have to love, you know, their kids growing up to adulthood and, you know, going to school, hopefully, in, you know, something that’s not a Madrassa.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Yeah. Along those lines, I have friends on active duty today. One of them has done seven tours over there and a helicopter pilot. And he told me initially when they went in to Iraq and Afghanistan, one of the missions was to destroy the poppy fields, stop the drug trade. And so there was a move to destroy all these poppy fields.

Then I got a photograph from him where he had sent a poppy back to his girl — his daughter in the States, and the Marines landed in the poppy fields. They were just moving out through the poppy fields after the Taliban, and that then kind of went by the wayside to destroy the poppy fields.

Can you address that a little bit, what they’re doing with that or — because perhaps poppy production is more economically feasible for them than doing rice and wheat and corn and that type of thing.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah. You know, this sort of war on drugs within the war on terror is an interesting thing. There’s a lot of parallels to our sort of, you know, war on drugs in the western hemisphere.

In my experience — in my time in Afghanistan, we did not engage in eradication efforts and we left that to other, you know, U.S. Government entities. The DEA was pretty heavily involved. There was a narcotics affairs section which was fairly robust at the time in Afghanistan. And basically, they were doing the same thing we were doing, but just with the Afghan counter narcotics forces.

So we were training the Afghan National Army and some of their sort of basic special operations unit, building capacity and capability in those guys, and combat advising them out in the battlefield. And the DEA was doing the same thing with the Afghan counterparts. So there’s narcotics — they’re counter narcotics guys.

But the issue is the same as it is here. I mean, there’s a supply and demand for, you know, raw poppies and opium to support the — you know, the global heroin trade. And, you know, as long as there’s a market, there’s going to be a producer.

The unfortunate thing with Afghanistan is that at the time, in the early 2000’s, the Taliban had been pretty — that was one thing that they did do successfully, and I guess if you’d call anything they did good, in a positive way was they — because they felt it was anti-Islamic, they had banned the production of poppies and opium production.

And so — and at the same time, there had been some efforts worldwide to clamp down on the production of poppies in Burma, in Thailand. The Thai and the Burmese governments were pretty successful there. And the Pakistani government was pretty successful in Pakistan kind of eradicating the poppy production.

So 911 happened, the Taliban collapsed. You had, you know, stable governments in Thailand, Burma, and in Pakistan, or a fairly stable government in Pakistan. So all of a sudden you’ve got this vacuum in Afghanistan and it was just filled again with this massive amount of poppy cultivation.

And the Taliban changed their tune. They changed their information, you know, their messaging because they were in need of cash. I mean, we had pretty much eliminated, you know, the support that they were receiving, at least in the early 2000’s from the Middle East and from al-Qaeda.

So they said, okay, now poppy — the production of poppy and support of the — us, you know, the truth seekers and the sort of standard bearers for Islam is now allowed. And they actually bankrolled a lot of the farmers and a lot of the low-level guys in the production chain. So now it was legal — or it was authorized in these un-governed areas that the Taliban controlled to produce poppies and it was a lot more profitable than other crash crops. You know, whether it was wheat or, you know, they do a lot of nuts and, you know, almonds and things like that and maize, things like that in these rural areas in Afghanistan, but all of a sudden, they can make ten times more profit with the cultivation of poppies, or the, you know, baseline production of opium or in some cases heroin.

So the local population, they’re kind of caught between a rock and a hard place. I mean, it’s a hard scrabble existence to begin with, and now they’ve got the Taliban telling them, hey, we’ll — you know, if you produce poppies for us to help us bankroll our operations, we’ll front you the money. If the crop fails, you’ll still get —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Still get the money.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — you’ll still get the money.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Subsidized.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. If, you know, whoever comes and burns a crop, you know, as long as you don’t — as you long as you put up some kind of, you know, effort to stop them, even if it’s just a verbal thing, then you get to keep the money. And then that’s a hard thing for us to match — for the West to match. I mean, we’re talking about, you know, long-term sustainable agriculture projects, you know, like planting cherry trees and, you know, more sort of basic food stuffs, but the profit is just not there.

So this farmer who’s illiterate and has got no education at all, I mean, he’s going to look out for his family by providing them with more money and more — you know, more sustenance and he’s going to look out for his family by having this sort of protection from the Taliban. So it’s an unfortunate thing.

And, you know, now we’re sort of — I think we’ve changed our strategy on, you know, eradication or, you know, the poppy production multiple times. I think — and my time in Afghanistan is somewhat dated — we’re actually, you know, pursuing it fairly aggressively at this point for the simple reason that, you know, the same networks that, you know, do the drug trafficking and the drug distribution are, you know, sort of the the same malign actors that, you know, support the precursor materials to the improvised explosives, whether it’s fertilizer or the — you know, the spider devices that, you know, the Taliban uses or the counting network uses to build these improvised explosive devices. You know, those same networks are — you know, they’re trafficking money, trafficking drugs, trafficking weapons. And so, you know, in order to attack those networks, we have to go after the drugs because that’s where a lot of the revenue comes from.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Revenue, yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: And a lot of those same, you know, infiltration routes that the drugs move on is where those other materials, you know, for the Taliban and Ikanis moved, so we need to attack those networks.

But again, it’s going to be a long road with the drugs. Interesting though, you know, the Pakistanis still have had a — for as many issues as they have there with governmental control of some of these distant, you know, places within Pakistan, whether it’s the frontier areas or the northern areas, they’ve actually still done a pretty good job with the poppy — with controlling the production of poppy and drugs. And they have some pretty stiff penalties like the Chinese do, for drug trafficking, or, you know, even drug possession in some cases.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, Jeremie, in 1961, I flew into Karachi, Pakistan on my way to Arabia, and I didn’t have time, but one of the things I always wanted to do was the romance of Richard Kipling, go up the Khyber Pass. I didn’t have time to do that, but I was told even 50 years ago, that was a pretty tough place to go — personal security.

Now that we’re drawing down from Iraq, we have tremendous supplies in Iraq and we have to get them transported into Afghanistan. And did you observe any of that transportation of equipment through the former Soviet Republic and back into Afghanistan because it’s a tremendous logistic thing to support Afghanistan.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. Yeah, I did. You know, that’s one of the primary missions of the embassy in Pakistan besides the diplomatic engagement with the Pakistani government, is to ensure that those lines of communication are maintained and we’re able to resupply. You know, now we’re down to 60,000. At the height of the surge, it was about 100,000 U.S. Troops in Afghanistan. Probably 160,000 with our NATO allies.

So a huge logistical challenge and, you know, all that stuff can’t come in through central Asia, necessarily. It’s a lot easier logistically to go through Karachi and then to go up through the Khyber Pass to the main base there in Bogaram, which is kind of outside of Kabul, or go through the Bolan Pass and up through Kwada, Pakistan and up through Chaman, which is another port of entry into Afghanistan, and then to Kandahar.

So, you know, everybody says, well, hey, let’s — you know, the Pakistanis aren’t our real allies and they’re sort of double dealing in these engagements with us. And those things are all true; however, you know, we need Pakistan, at least for the near term because we have to maintain the ability to transit through Pakistan to resupply our troops in Afghanistan.

We’ve recently — after the Osama bin Laden raid where things really flat lined in terms of our relationship with the Pakistani government and the military, opened more networks to the north, but very costly. You know, all that equipment has to transit through the former Soviet Republics. The Russian Federation has a lot of control and say to that, and they could just as easily turn that tap off as the Pakistanis could.

So it’s expensive to use that route. It’s much cheaper to go through Karachi and then through Pakistan.

Additionally, you know, we fly a lot of our — a lot of our air routes from the Indian Ocean and from the Middle East. So, you know, when we fly off an aircraft carrier to support combat operations in Afghanistan, or we fly a B-52 bomber for — to drop some bombs in Afghanistan, a lot of those come out of either the Gulf or Diego Garcia or off an aircraft carrier. And because Afghanistan’s land locked, they have to get — we have to have these over flight authorities to get there. And clearly, we’re not going to oversight authorities from the Ukrainians. So it has to — you know, we can’t choose our allies and we have to, you know, go with who we got, and the Pakistanis are pretty much it. So we rely on them heavily.

In terms of day-to-day operations, or those lines of communication, you know, the Pakistanis provide security for those convoys and it’s everything from, you know, humvees to containers full of food. Not a lot of lethal aid. That stuff usually goes by air, but it’s — you know, all the things we need to sustain the Army outside of weapons and ammunition and the Marines.

So interestingly, the Pakistanis would sort of use that as a tool for leverage. When relationships were bad, there would be a lot of attacks on those convoys and a lot of — you know, burning of vehicles and things like that. When relationships were good, the Pakistanis would provide more security, would negotiate with the tribes to make sure that they stayed away from the convoys out in the federally administered tribal areas in (ph) that used — formerly known as northwest frontier province. And so the stuff would largely go through unmolested.

And, of course, after the Osama bin Laden raid, the routes were closed completely for months. And then there was another — we would call it a blue on green where American forces and Pakistani forces engaged each other on the border and, you know, the Pakistanis are always going to lose in that engagement just because they don’t have the technology or the weapon systems. And about 21 of them were killed by American forces.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Uh-huh, I remember that.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: So again, they closed those G-locks down and, you know, very difficult diplomatic time.

But, yeah, it’s something. And up there on the frontier, I mean, it’s — you mentioned, you know, Richard Kipling. I mean, it’s a lot of the unchanged from that era. I mean, the interesting thing about the Pashtuns, which, you know, there’s a lot of very interesting sort of, you know, ethnic study about that, anthropological study about that. You know, they say at some level they’re descendents of Alexander’s army when he moved through Afghanistan, you know, 1,000 years ago. They are split between Afghanistan and Pakistan based on that Durand Line, which was sort of an arbitrary line based on some high peaks that the British governor of India and his surveyors assigned sort to have the — delineate the boundary between — what was India and Pakistan, so that you sort of split the tribe. And the Pashtuns are the largest tribe on earth, you know, millions and millions of people. You sort of split them down the middle. And they’ve always made their living by controlling those passes, controlling those lines of communication, engaging in, you know, collection of tolls or extortion or banditry, and it’s still very much that way. And with the sort of decrease in control in that part of the world based on, you know, the Pakistanis not being able to really generate enough combat power or enough will to sort of, you know, bring the tribes under some degree of control, and then a war going on in Afghanistan, it’s probably as dangerous a place as it’s ever been.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, we’ve been discussing tactics. And one of the things I just want to mention in passing. I was in nuclear weapons in the Marine Corps, employment officer, and very, very into that group of people. And my concern — it’s a strategic one — is that we have support of Pakistan and provide it nuclear weapons, same to India. Iran is attempting to get nuclear weapons in North Korea. And then we have these things on in Israel. And my concern is the control of these nuclear weapons in Pakistan and India. It used to be that Pakistan and India were fighting each other, but in the back of my mind, you know, I’m very concerned about the security of those.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: And that’s just an issue that I kind of study quite a bit and that’s another thing for another day to talk about.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, yeah, and — well, I can — you know, I can sort of discuss it generally. I mean, we — you know, that’s one of the big fears of the Pakistani government and the Army is that, you know, any American there is — has designs on, you know, getting access to some aspect of their nuclear program. And that — I can say from my experience, that’s not — that’s not true. You know, no part of our charter at any time when I was there was to collect any information on the Pakistani nuclear program.

But clearly, it’s a point of concern for the — for not just the U.S., but for the world. With Pakistan, there’s a couple of issues. One is that they don’t see Islamic militancy is their primary threat. They see India as their primary threat based on the partition of —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — of India and Pakistan in 1947 and the sort of holocaust and genocide that occurred as part of that, on the part of both sides, the Indian Muslims and the, you know, the Hindus and the Sikhs in India. So there is a lot of — it surely was a genocide, but the Pakistani as sort of as a point of departure in any discussion about their national security want to talk about that and want to talk about how important it is that they have nuclear weapons to keep India — this evil India at arm’s length, and the nuclear weapons are clearly part of that strategy.

So it’s something of concern in that regard. And clearly, it’s not a military effort; it’s a diplomatic effort to engage in, you know, discussions about non-proliferation and those kind of things, between India and Pakistan.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: And that’s one of the sort of schizophrenic things about Pakistan that is so — it’s so unnerving is that you know, they’re — in anything they do, you know, the cliché is that they’re 50 percent irrational and 50 percent emotional in their response to things. So that would be a concern for anybody with the proliferation and that’s why we need to engage with them.

For the — the other part of it is that, you know, they haven’t had the best reputation in their nuclear program for safeguarding nuclear technology. Aukicon (ph), who is sort of the god — he’s sort of the, you know, the godfather of their program, he has shown a propensity to allow proliferation in this technology, at least at some level to the Iranians, to the North Koreans, and so has not been a good steward of — you know, of that technology and that’s another reason for concern. You know, how secure is the knowledge of how to make these bombs, or how to, you know, refine uranium. So that is a fear.

Although I will say within the Pakistan, the idea of a loose nuclear weapon is not something that I think is a high probability. The Pakistani military is not great at counter insurgency and is not great at a lot of things, but it is a professional army. You know, one of the biggest armies in the world, 600,000, I think, ‘ish got active duty, you know, men under arms mostly in the army. And they have their best and brightest on the protection of that nuclear — the weapons themselves. So I’m not that concerned about, you know, a lost weapon, although it’s not beyond the realm of impossible.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Something I keep an eye on.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Jeremie, President Obama has indicated that by the end of the year 2014 — 2014, that’s two years from now, we’ll be out of Afghanistan. Now, throughout history, Alexander the Great couldn’t conquer and hold Afghanistan. Afghanistan is known is the graveyard of empires. The Russians couldn’t hold on there. The British couldn’t hold on there. And we’re leaving. And what is your prognosis of the future for Afghanistan as we pull out and then after we leave?

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. I don’t — I’m not very optimistic about, you know, the nation state of Afghanistan, you know, enduring for any period of time after we depart. I mean, the capacity and the capability we’ve built in their military is good, but it was from nothing, and it was an effort that the Soviets tried back in the ‘80s, you know, and put a pretty good — pretty concerted effort against. So I don’t think that — I don’t think that these security apparatuses or forces that we put together are going to endure in every part of the country.

I think in the north — you know, where the northern alliance was prior to 911, it’s more sort of a — ethnic Tajiks, Uzbeks, and the Hazariis, who are sort of the Asiatic — Asiatic group in Afghanistan. I think that there will be, you know, some residual state in that — in those areas. I think that they have a better — a better future as sort of a nation state.

For the Pashtun areas, I don’t see it. I mean, I don’t think that they want to be part of a country. I don’t think they want to be part of a democratic process outside of the conventions of the tribe. I mean, that’s a democracy at a certain level. But I think that they want to — I think that they want to maintain their power base. I think they want to maintain their tribal structure. They see anything that’s outside of that as a threat to that structure.

So I think you’ll see that sort of revert back to the — you know, it’s either lawlessness or sort of some version of Taliban control, not — you know, not long after we depart. And maybe that’s good enough. I mean, in certain parts of the world, I mean, we’ve seen it over and over again. It’s kind of the — you know, it’s the prophecy that keeps getting fulfilled, whether it’s, you know, Somalia or sort of these ungoverned spaces in west Africa or Afghanistan or the tribal areas in Pakistan. I mean, you know, an acceptable level of violence is probably good enough. And I think so long as we don’t, you know, have a threat to the homeland, you know, another 911 type attack, I think that that’s acceptable; particularly after the efforts we’ve made today.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Efforts we’ve made.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: You know, it’s not — I don’t want — you know, nobody likes to say that it was futile and it was sort of lives lost or nothing, but, you know, I don’t think Afghanistan as a nation state has any hope of enduring. And I think our engagement there, regardless of what President Obama says, is going to be longer than 2014. I don’t know if that means it’s going to be with Special Operations Forces and predator drones and, you know, operational strategic targeting. That’s what I think it will look like, but I don’t — I don’t — you know, I can’t speak for the President or the Government.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, there are a whole lot of geopolitical issues here. And I just recently re-read James Michener’s book entitled Caravan. So he wrote it in 1946 and that was before the partition in India and it used to be — it’s now Pakistan on the border — how the tribes would go from India, Pakistan, through Afghanistan, up to the Soviet Union — Russia — trading and coming back and forth and that was sustained. And they had no regard for the boundaries. They just went through there and they survived and I think that’s how they’re going to survive in the future —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — in the tribal history of what they did hundreds of years ago.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah, I would agree. I would agree. You know, there’s some dynamics. I mean, there’s some — you know, a lot of people argue that, hey, the Soviet invasion sort of destroyed Afghan society, Afghan culture, the identity of a nation state. But if you really read back to the, you know, the times of, you know, campaigning by, you know, Gengkis Khan and the Mongols and these other empires through Central Asia, I mean, Afghanistan’s been destroyed, you know, I don’t know if hundreds of times, but tens of times by invading armies, inner — you know, inner-tribal violence and I think that that will endure, you know.

And really, I mean, I think our — from our standpoint — I mean, the American standpoint, maybe not with a lot of combat troops on the ground, but, you know, we need to continue to engage, and we need to continue to engage in Pakistan as well. You know, I don’t know what that engagement looks like with the draw down and, you know, our budget and our ability to subsidize a lot of things, clearly it’s going to be significantly lower than it is at present, but, you know, we’ve got to stay engaged.

And that — you know, that’s — regardless of what our, you know, trading interests are, economic interests, we’ve got to look beyond the next four years or the next election cycle and look at long-term priorities and goals. And I think that they will — you know, if we’re on the right track, we will endure with our engagement in Central Asia and that part of the world.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, America’s going to be watching, Jeremie.

So we’ve got that phase of the interview concluded. However, we’re sitting in Aspen and you’re back adjusting. I was in the same position as you were 20 years ago and I wound up having a career in skiing and I know you’re looking, and we’re here to, you know, help you get adjusted and I know that you will. And one of the things we welcome you to is the Veteran’s community and we’re real pleased that you’re attending the Veteran’s ceremonies and you’re a member of the Elks and a member of the community, getting your children in the school and Sally’s with the ski club, so we’re very happy that you’re home safely with us. And so you have a very bright future here. You served your country well and we thank you for doing that.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, I’m — you know, I appreciate that, Dick. I’m happy to be back in the valley. I always kind of hoped I’d end up here, so, you know, we’ll see.

And on the note of kind of Veterans — you know, these Veteran’s groups and a lot of the things that you’ve been heavily involved with and really, you know, led through the — you know, through some — I would say probably some dark times, particularly in the — you know, as we spoke of earlier, you know, coming out of Vietnam. I mean, I remember as a kid in Aspen, you know, it was a pretty liberal place. It was a pretty hippy-dippy place, you might say and, you know, not very supportive of the military.

Some of the sort of pillars of the community, or at least our elected leadership, were particularly unsupportive of the military, which is their prerogative, but it’s great that you and a lot of other — or I should a few other, you know, committed sort of Veterans persevered through that and, you know, got the memorial established there next to the courthouse and some of these outreach programs which have just really grown.

I actually was — you know, as a kid, was one of the — attended the first ceremony there on Veterans Day and that was really kind of a breakthrough. I don’t think a lot of people wanted to talk about —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Took me ten years to break through when that memorial came.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right. A lot of people didn’t want to talk about Vietnam, didn’t want to talk about Korea, you know. Didn’t — you know, even in some cases, didn’t want to talk about the Second World War. But I think it’s great that we’ve kind of moved beyond that, and the community I would say as a whole here, has changed in a very positive way in that regard with outreach to Veterans.

And, you know, I would say — I mean, I had a different experience than anybody else. I mean, every Veteran’s experience in war is different and their experience coming home is different. You know, I was a 35-year-old man to 40-year-old man, you know, who was fairly — had kind of seen a lot of life and then seen things before I went to combat. That is a different experience than an 18-year-old kid who doesn’t have a lot of life experiences and sort of this is it. I mean, this is high school and basic training and combat.

So it’s going to take — it takes a lot of different tools to engage these different experiences and these different, you know, issues that guys come back with. And so I — you know, I’m looking forward to being involved in that here in the valley. And I think that, you know, you guys have set a great, you know, example and so I hope to carry that on in whatever capacity.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: We’ll be bringing you into the fold.

I think we have to remember who went before us and I’m speaking specifically of the 10th Mountain Division of how those Veterans came out and got Aspen going, the ski industry, Vail, all of them. And then the 10th Mountain Hut Division, which Kurt — or Fritz Benedict and they got that — Steve Knowlton, those guys got it going. Everyone enjoys that.

And now where we’re expanding now with all the Veterans coming home with PTSD, we’re reaching out in the Valley through programs through the Aspen Institute, through Purple Stars of helping families where the suicide rate is very high. We’re working on that.

And then beyond that, at the end of life, we work with the Hospice. Just before Veterans Day, we went out, our committee — Darrell Grobe and Dan Glidden and myself — with the Hospice, we went to eight Veterans homes on the Friday before Memorial Day, just about ten days ago, and we gave these certificates to the Veterans thanking them for their service. It was from the Veterans Administration and from the Hospice. And we went over here to Jim Hayes. He’s 92 years old. And he said that he — this is the first time anybody had ever thanked him in 67 years for his military duty. So we’re going to the other end of the spectrum.

And then we went to two other Veterans, Hans Lull on that Friday and gave him his certificate, and he had a great smile on his face and was very appreciative. And then two days later he died on that Sunday.

And then we went to — down there to the rest home in Carbondale and went to a World War II Veteran there and gave him his certificate, and he was so impressed. He said, “Holy smokes, what we — I appreciate you coming here,” had a big smile on his face, and he died seven days later. So we’re reaching out to the — thanking these Veterans, especially the older ones that are about to leave us. And so that’s the things that we’re working on and I’ll be talking more about —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Right.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — helping us —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Yeah.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: — we need some help.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, and that’s — you know, off camera we talked about that earlier. The Veterans Affairs — Department of Veterans Affairs has come a long way and I don’t want to minimize the effort that has been made, particularly since 911, to sort of help Veterans reintegrate into, you know, being a civilian and being a productive member of society, and taking care of medical needs and — whether it’s physical injuries, mental health. So the VA has come a long ways in that. But, you know, I’m the last guy after just coming out of 22 years of it to advocate for the Government to come and they’re going to save the day in any regard.

I think that the best thing for Veterans is engagement at the community and the individual level, and that’s something that every — you know, in my view, I mean, it’s kind of every citizen’s duty, whether they’ve ever served in the military or not, to not just, you know, thank a Veteran. I mean, that’s a great start and it’s appreciated, but to really make a concerted effort to help guys to feel like valued members of the community and of society and, you know, make sure that, you know, we’re taking care of each other.

And I think that the efforts in the Valley are a great example of that. You know, I mean, the guy that’s on the fence with, you know, hurting himself or, you know, committing suicide and we’ve got a huge number of Veterans and active duty soldiers that are taking their lives due to post traumatic stress or whatever reason, you know, and maybe the difference between that guy hurting himself and not hurting himself is somebody talking to him, you know, and that’s not somebody in a clinical environment always, in my view.

So that’s a start, you know, some of these programs and monies to help, you know, make guys feel good about themselves regardless of their physical or mental disabilities is another great thing, and I know there’s a lot of philanthropies in the Valley that support that.

And, you know, there’s a lot of — you know, I’ll be honest, there’s a lot of money in the upper Roaring Fork Valley that could be used through non-profits and through programs to help Vets. And that’s — you know, that’s — you know I think that that’s — that is a great change in — that I’ve seen even in my time in the military is the outreach and the welcome back that I’ve gotten and certainly, I — you know, I gave something but I didn’t give everything like our

— you know, some of our wounded and, you know, KIA’s —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: KIA’s that came back.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — and their families that, you know, those guys we need to take care of them. And not just the service members, but the family —

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: The families back here.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: — the family members as well.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: Well, I’d like to thank the community here for all the support that they’ve given for the wounded warriors, the disabled American Veterans winter sports clinic. The whole community, the Elks, everybody helps out when they come to town in March and April, the shooting range in Basalt, and the skiing and the snowmobiling and all that.

And I’d like to just ask everybody, you know, that when you see a wounded warrior, reach out to them. Through Challenge Aspen here, we’re bringing in a lot of the wounded warriors and training them for the U.S. Olympic disabled team. And on Saturday, I just happened to be at Sacks Coffee Shop in Basalt and there was a man in a wheelchair there, a young guy, and I thought, well, you know, I was drinking my coffee and I walked around behind him and it said wounded warrior. And so I thought how could I not engage the wounded warrior. And I got to talking to him, and he was wounded in Afghanistan, a warrant officer helicopter pilot. And four years ago he came here to the winter sports clinic and learned how to ski. He’s from Georgia, never saw snow really. And he got really involved with skiing and now he’s a member of the U.S. Olympic team of disabled that go around. There’s five of them living here this winter. And so, you know, talked to those guys. They compete in Canada, all over the United States. Not only does he do competitive ski racing, but he’s a competitive bicycle in Europe.

And so we’re doing a lot to help change the lives of people that would never have been brought to the things that we enjoy in this Valley, the outdoor life and the skills. So we are doing a good job and we’ll continue to do that.

So I’d just like to read this one little statement here that, the Roaring Fork Veterans History Project exists to capture the personal stories of Veterans of all wars, especially those Veterans whose stories may soon be lost. To support this important community project, please contact Lieutenant Colonel Dick Merritt, United States Marine Corps, at (970) 927-5178 or email merritt — m-e-r-r-i-t-t — 1@q.com.

And, Jeremie, we want to thank you for coming in here today and bringing us — and then the community — this will show on GrassRoots — to hear about your views of having served our country in Bosnia and Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan. And this is a pin that I support the Roaring Fork Veterans History Project.

Thank you, Jeremie, for being here.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL OATES: Well, thank you, Dick.

LIEUTENANT COLONEL MERRITT: See you in the community. Thank you very much.